Back in the mid '90’s, with the web in its infancy and bulletin boards springing up to connect bike riders from around the world, avid fans of the racing bike were soon swapping gossip and rumours that a lot of the high-profile brand names, the ones with names ending in vowels, were not quite as they seemed. Stories were traded about so-and-so's frames actually being built by so-and-someone else. Speculation was rife about who actually built what, and it all added to the fun of those early days on the fledgling World Wide Web.

Back in the mid '90’s, with the web in its infancy and bulletin boards springing up to connect bike riders from around the world, avid fans of the racing bike were soon swapping gossip and rumours that a lot of the high-profile brand names, the ones with names ending in vowels, were not quite as they seemed. Stories were traded about so-and-so's frames actually being built by so-and-someone else. Speculation was rife about who actually built what, and it all added to the fun of those early days on the fledgling World Wide Web.

Nothing new of course; in the '50’s, legends were created and spread by word of mouth from artisan builders, housed beneath velodromes and building frames for the shining stars of the age.

In reality, the big name manufacturers would contract a relatively unknown but highly regarded local frame builder to look after the custom-built wishes of their star rider, leaving them free to concentrate on the volume production. Sometimes, the big boys would reap the glory - and the sales - after a Classics or Giro win. Sure, contracting-out was an expense; but with the right rider on the right bike, it was a profitable one. So the system carried on, and an unwritten "code of honour" between both sides meant glory and riches for the big boys, bread and pasta on the table of the frame builder.

Result? Everyone went to bed happy, and every now and then the cognoscenti with inside information would go in search of the work of the artisans themselves, not the brands who supplied the logos.

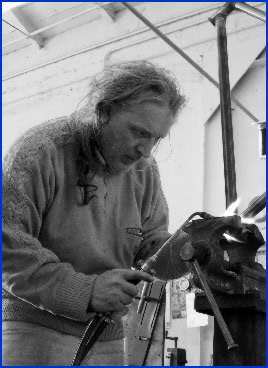

Then in 1995, the UK's Cycle Sport magazine ran a story about a contract frame builder based in an old farm building near Verona. At the time, Dario Pegoretti was a name little known outside Italian bike trade circles and pro team equipment managers. He had set up on his own a few years earlier after 15 years working with Milani, a Veronese contract builder with a reputation for being both productive and innovative in his approach to semi-custom building techniques. Dario soon built up a rep in his own right within the closed world of the Italian framebuilding scene, and Cycle Sport was only too happy to let us all in on the secret.

While Dario was discreet, Cycle Sport left the reader in no doubt of the calibre of riders in the back pages of the Pegoretti order book. It didn't take much deduction from the hints dropped to figure out that this was the guy who was building frames for the likes of Indurain, Chiapucci, Bugno, LeMond and a host of other star names. Almost overnight a new name - and yes, one with that all-important vowel at the end - was suddenly propelled to the top of the wish lists of Italophile and "wannabe" bike riders throughout the English-speaking world.

The attraction with Pegoretti, the thing that set him aside from countless other bike brands, was that Dario did it his way. He set out his own tube diameters; he made his own dropouts; he worked with TIG. He built horses for courses; for someone like Bugno who needed strength and resilience for the Belgian Classics he'd use oversize, thin wall, chrome-vanadium steel. For a big, powerful rider who was looking for every tweak of his bike geared towards storming up the Alps - an Indurain, for instance - he'd build using heat-treated alu. This was just what people were looking for at a time when almost everyone used lugs and almost all used 25.4/28.6/28.6 tube configurations.

The attraction with Pegoretti, the thing that set him aside from countless other bike brands, was that Dario did it his way. He set out his own tube diameters; he made his own dropouts; he worked with TIG. He built horses for courses; for someone like Bugno who needed strength and resilience for the Belgian Classics he'd use oversize, thin wall, chrome-vanadium steel. For a big, powerful rider who was looking for every tweak of his bike geared towards storming up the Alps - an Indurain, for instance - he'd build using heat-treated alu. This was just what people were looking for at a time when almost everyone used lugs and almost all used 25.4/28.6/28.6 tube configurations.

However, unlike those before him, his sudden success and new found notoriety didn't mean a rapid expansion in production. Dario stuck to his guns and kept production limited to a manageable level, while resisting the temptation to cash in by contracting out to other builders.

For Dario, the big bonus was having a steady stream of orders and a great distributor looking after his US sales. These factors together with his continued popularity allowed him the freedom to express his individuality, to try out new ideas. Going with his gut feeling and not having to pander to the mainstream bike trade he introduced models with names inspired by Steve Earle album tracks (CCKMP) and obscure R&B references (Great Googly Moogly). Paint designs inspired by contemporary art were to follow and despite quizzical glances from the mainstream, this new approach appealed a whole new group of admirers and owners; the ones who knew their Gilbert and George from their Black and Decker.

These days, Pegoretti customers tend to be divided between lovers of the traditional elegance of his Luigino model, a lugged, steel beauty that shows off the skills nurtured at Milani, or his latest avante-garde designs, the Responsorium. While the Luigino is universally accepted as a modern classic, it's the latter, named after an album by roots music ensemble The Dino Saluzzi Trio, coupled with paintwork inspired by Jean-Michel Basquiat, enfante terrible of the '80’s New York art scene that attracts more than its fair share of controversy.

Can a bicycle be art? Is framebuilding an art? The debate goes on. In a world of me-too, fashion-driven, global brands the work of Pegoretti occupies its own space and cannot be pigeonholed. It would be easy to define his work as merely carefully constructed, ride-oriented "tools for the job". In fact, Dario will be the first to reach for the 'Mythbusters' button; he's often quoted as saying "it's just a bike, it's not an airplane" and that "building a frame is a work made by sight".

In a world of me-too, fashion-driven, global brands the work of Pegoretti occupies its own space and cannot be pigeonholed. It would be easy to define his work as merely carefully constructed, ride-oriented "tools for the job". In fact, Dario will be the first to reach for the 'Mythbusters' button; he's often quoted as saying "it's just a bike, it's not an airplane" and that "building a frame is a work made by sight".

In this case though, it may just be the voice of modesty talking. As Richard Sachs will tell you "...what more can I say except that he (Pegoretti)has forgotten more than any of us (pretenders) here will ever know!" Praise from the highest level indeed. Further inspection will reveal that from the initial selection of raw materials to the final decal placement, there is evidence of Pegoretti's handiwork and deliberation throughout the production of his frames. Add one of Dario's inimitable hand painted designs, each one carrying its own unique brush strokes, swirls and daubs and what do you have?

In Pegoretti’s studio the bicycle becomes the canvas, the vehicle for his neo-expressionist artistic leanings. For some, this would constitute the work of an artist, but art by definition is highly subjective. And so the debate goes on.

If for you, Mondrian and Rothko just did colored squares or Keith Haring does nursery-wall Men murals, then skip the next bit.

If not, consider this. In a busy street in cosmopolitan North London sits Mosquito Bikes, a haven for bike connoisseurs. They’re the UK's sole Pegoretti dealer and regular visitors to Dario's workshop. A few miles south across the River Thames sits Tate Modern, a vast gallery built in the shell of a former power station and a Mecca for lovers of modern art.

You could spend an afternoon in either venue, in both fascination and contemplation of the works on display. Spend an afternoon in both and it’ll soon become apparent; a Pegoretti Responsorium is as much at home hanging on the racks at Mosquito as it would be hanging on the walls of Tate Modern. Art or bike? Both!

![]()